Inside Dallas Museum of Arts’ “He Said/She Said: Contemporary Women Artists Interject”

The Collin-Denton Spotlighter takes an inside look at the Dallas Museum of Art’s “He Said/She Said: Contemporary Women Artists Interject” and learns more about the exhibition from DMA Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art Ade Omotosho.

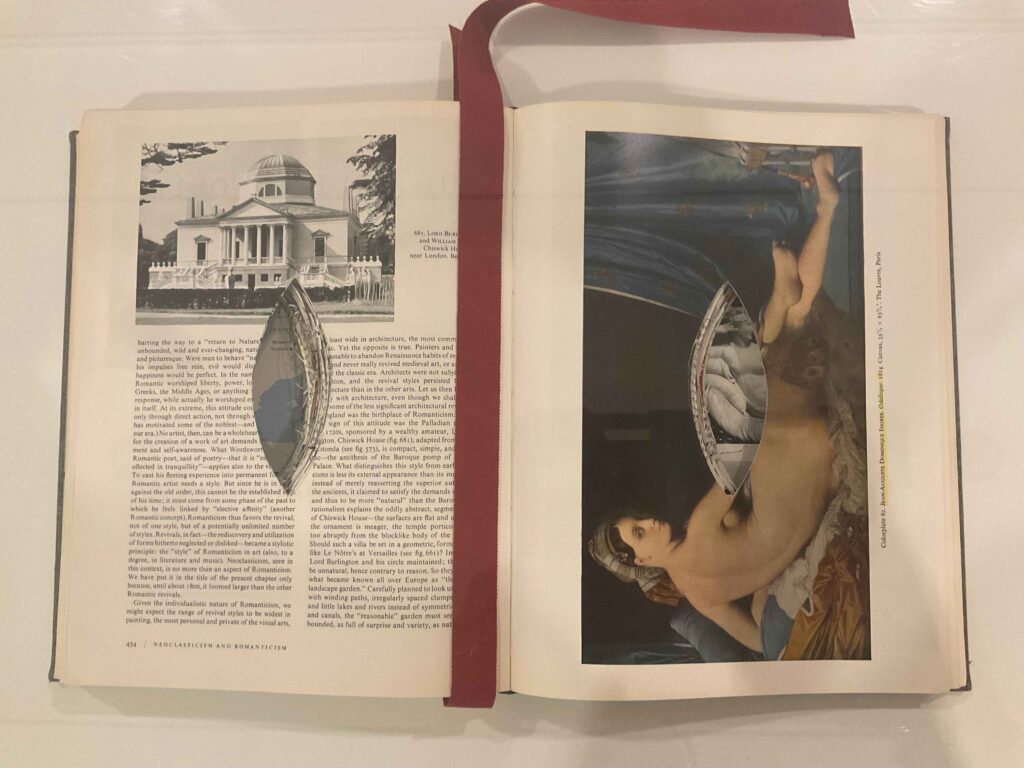

The textbook underneath the glass case inside one of the ongoing exhibitions at the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) omits so much more than its title would suggest. H.W. Janson’s 1962 “History of Art” is an influential, foundational textbook, yet no female artists appear within its pages. Dallas-born Kaleta A. Doolin spotlights that ignored history in “Improved Janson: A Woman on Every Page.” A cutout in the shape of a vulva creates a continuous representation of a nude woman on each page, displaying to would-be readers how past art history textbooks focus on the female form rather than the contributions of female artists.

“He Said/She Said: Contemporary Women Artists Interject,” open through July 21, spotlights women who claim their rightful place in art history while challenging misconceived norms and confronting themes of sexism, racism and gender inequality. The exhibition is akin to a walkable edition of a revised art history textbook, one that proudly displays the impact and influence of female artists from the late 1900s and challenges the myths and preconceptions surrounding the genius of male contemporary artists.

“The exhibition was beautifully conceived by Katherine Brodbeck, the DMA’s Hoffman Family Senior Curator of Contemporary Art. During her tenure, Katherine has done a great deal to acquire work by women artists, and this exhibition, which debuts numerous new acquisitions from the last few years, is in many ways the fruit of her efforts as well as those of Vivian Li, Lupe Murchison Curator of Contemporary Art,” DMA Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art Ade Omotosho said in an email interview. “As I installed the show, I was struck by the ways Katherine extended the premise of the exhibition to include an array of artists and aesthetic techniques. It’s a sharp approach to both rethinking and making demands on the art historical canon.”

Exhibition attendees find an encapsulation of that approach not only in Doolin’s reworking of “History of Art” prominently positioned at the beginning of the exhibition but also within Deborah Kass’ nearby “Making Men #3.” Omotosho described Kass’ painting as “in part a brilliant amalgam and reworking of the hallmarks of the styles of Jasper Johns, Robert Motherwell and David Salle on a single canvas.”

The exhibition pairs Kass’ painting with its referential works. Kass’ piece appears beside Johns’ “Device,” while Motherwell’s “Elegy to the Spanish Republic 108” remains readily visible in the following room. “In a way, Kass’s work captures the energy of the imagination as it works to metabolize various influences,” Omotosho said. “It asks: Who are my influences? How can I transform such influences in my work? What aspects of others’ influence do I discard or absorb?”

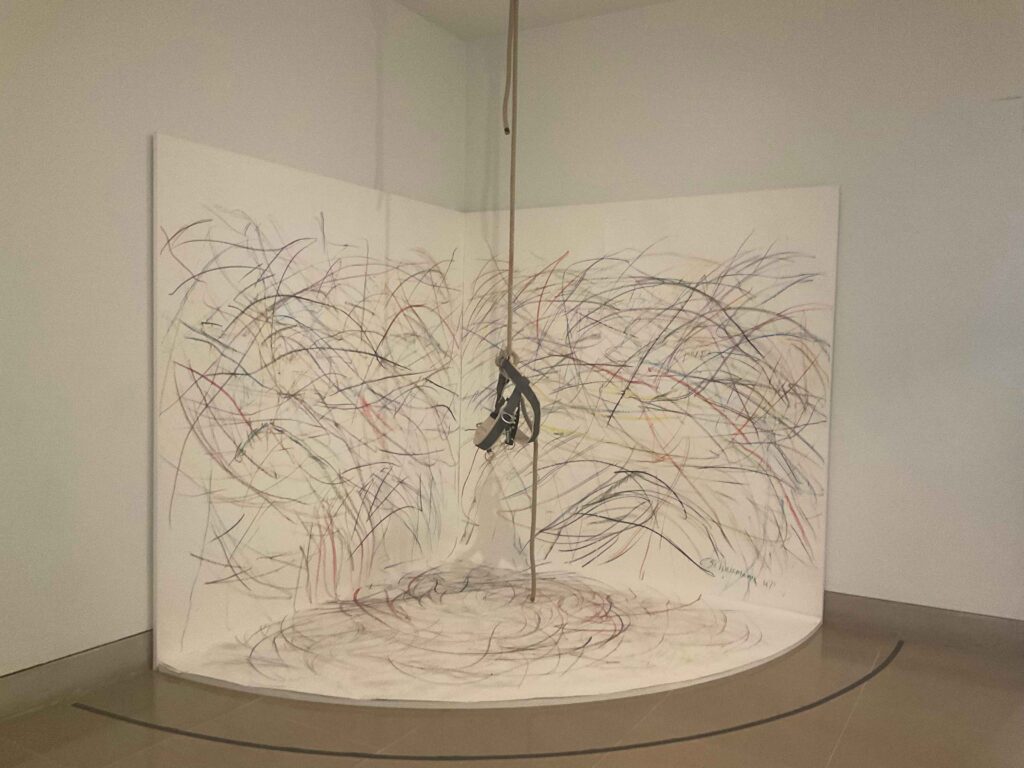

Similarly, a multi-faceted look at Carolee Schneemann’s “Up to and Including Her Limits” as well as Sarah Charlesworth’s “Yellow Action Painting Photo #3” positioned aside Jackson Pollock’s “Cathedral” exemplifies the exhibition’s confrontation of male privilege and the mythos of what it calls the “lone male genius.”

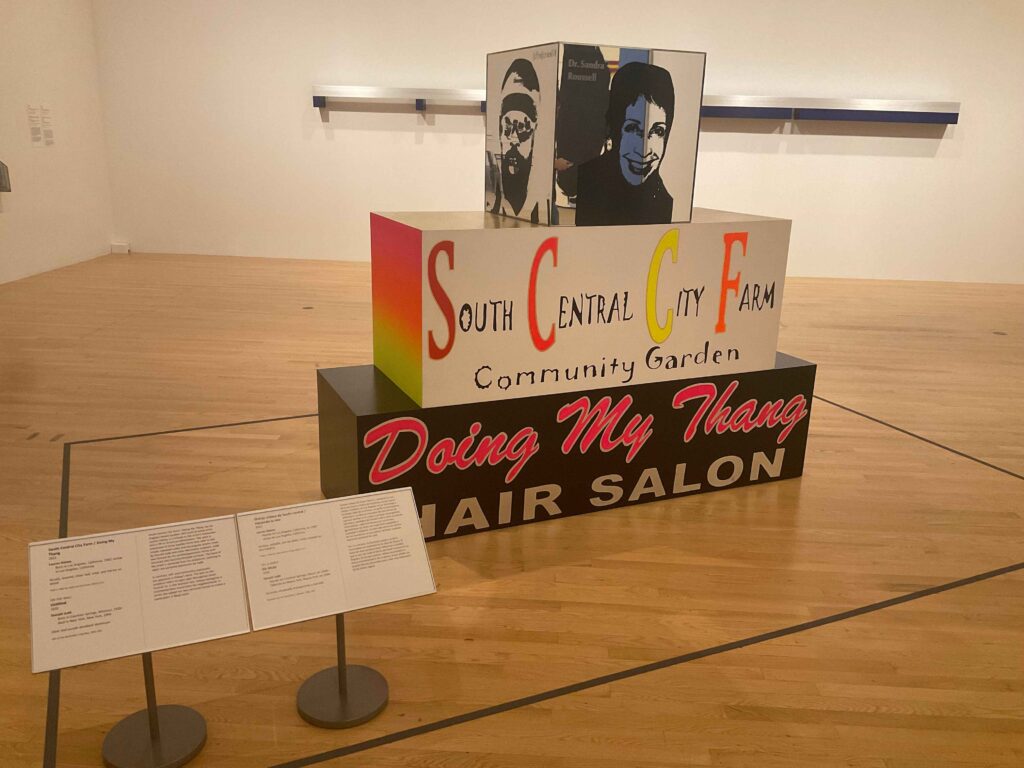

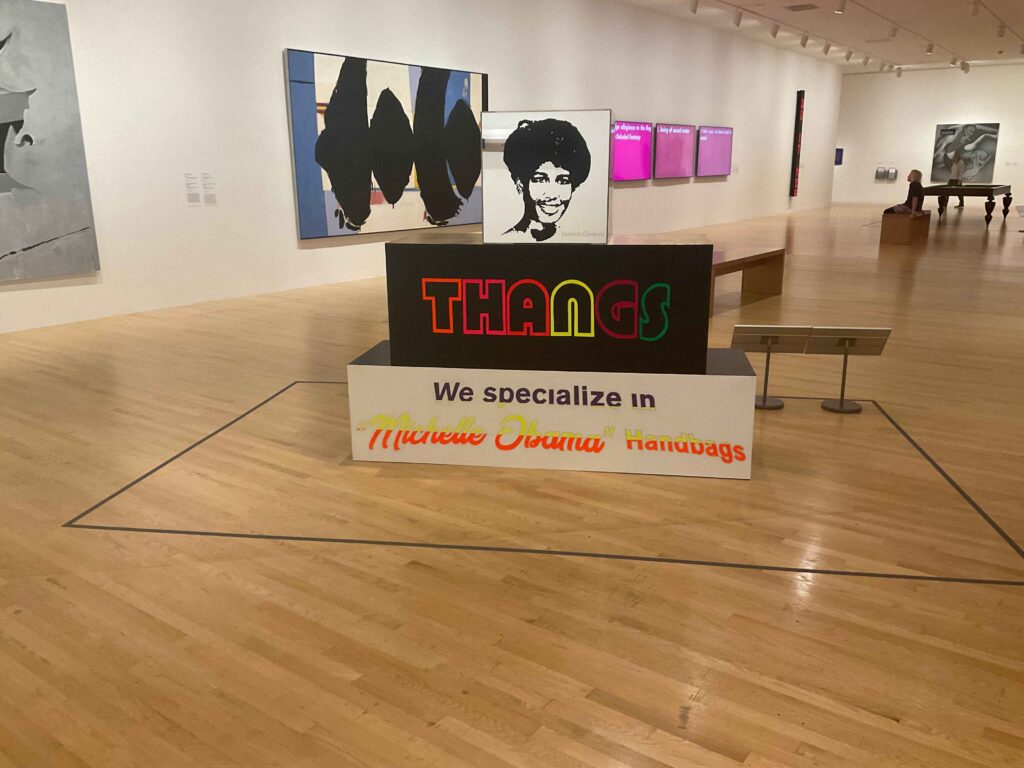

Upon entering the broader exhibition space, Dallas Museum of Art attendees continue to see the non-linear nature of “He Said/She Said.” The exhibition contains four interconnected sections in a loop: “Women and Appropriation,” “Women and Surrealism” “Friendship and Collaborations” and “Black Female Subjectivity.” Each section includes a collection of captivating, thought-provoking works.

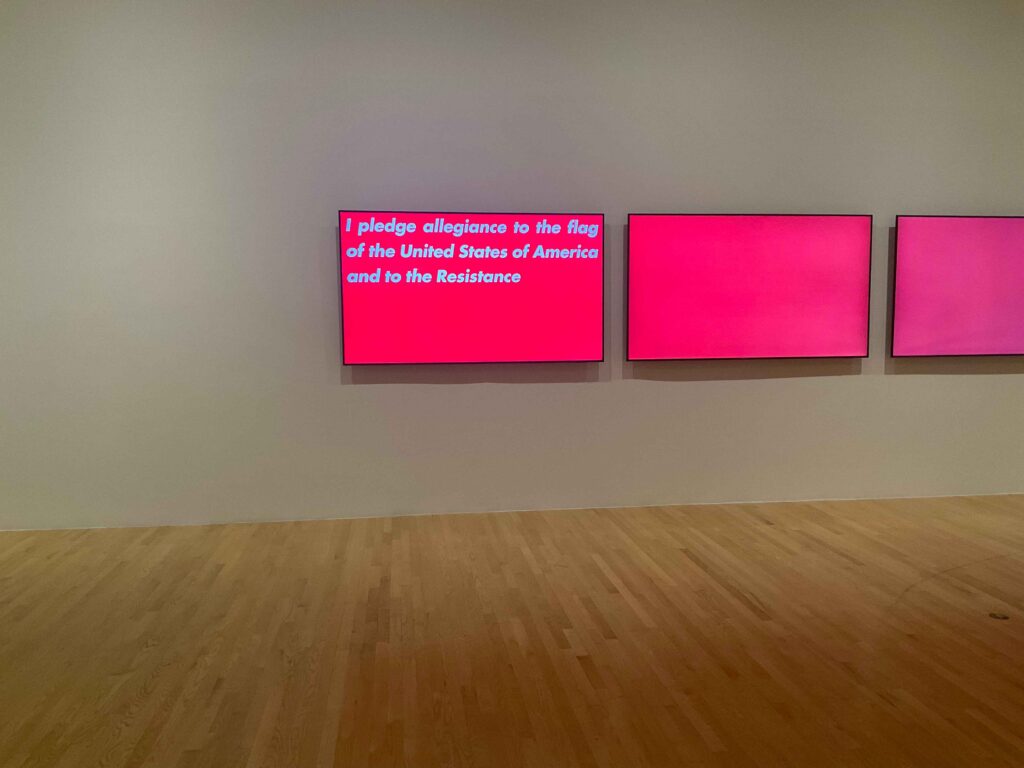

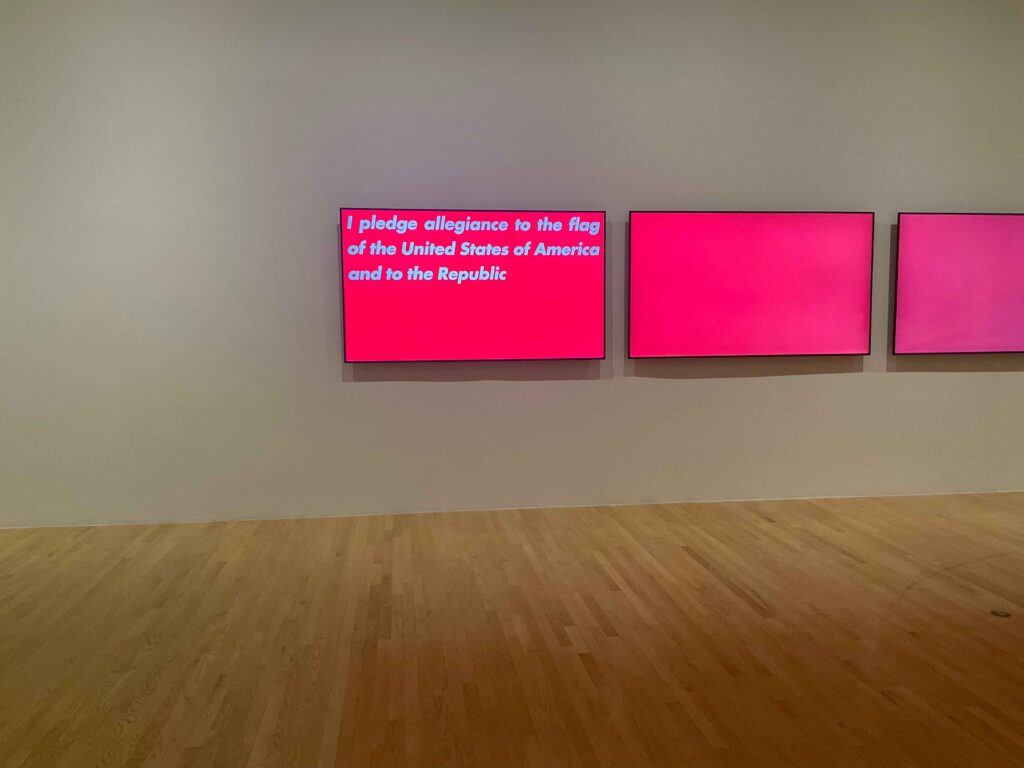

It’s easy to find yourself immediately drawn towards Barbara Kruger’s “Pledge, Will, Vow” when first entering that space. The bright red digital displays seem to beckon you to sit down and watch as the artist retypes the United States Pledge of Allegiance, legal estate documents and marriage vows to illustrate the inequities in our current socioeconomic and political systems. Likewise, Jenny Holzer’s LED display “I Am a Man” demands attention, with matter-of-fact statements on sex, life and death delivered through the sharp, bold medium.

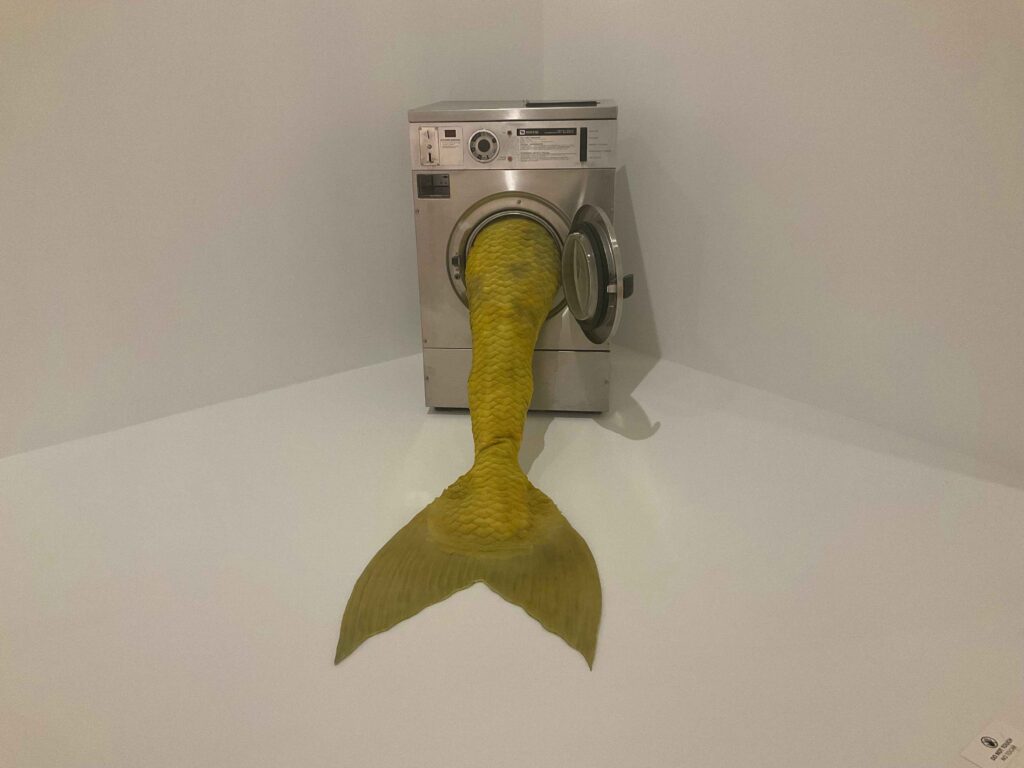

The surrealistic works of artists like Olivia Erlanger pull attendees further through the exhibition. Erlanger’s “Pergusa” pairs the mystical majesty of a mermaid tail with the stark contrast of a washing machine. The exhibition explains how the artist found inspiration in the implications surrounding a laundromat for different races, genders and classes, with the mermaid tail evoking the wicked, seductive stereotypes of women perpetuated throughout Greek mythology.

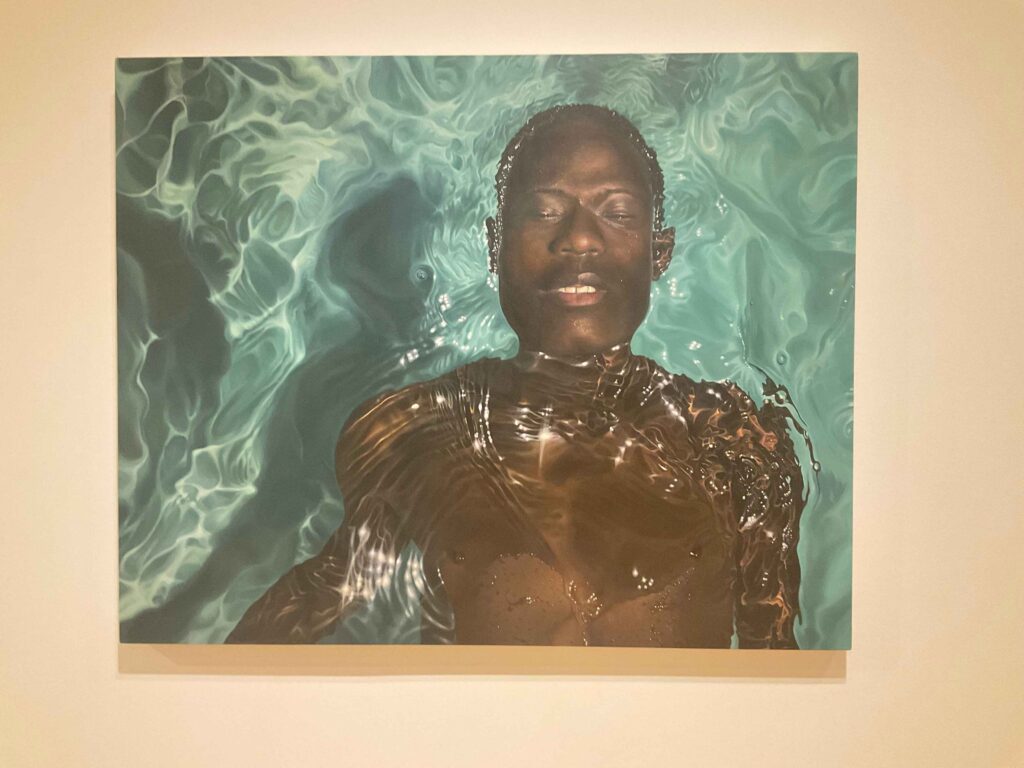

Almost in contrast to the surreal is Calida Rawles’ depiction of North Texas artist Diedrick Brackens within “In His Image.” Rawles’ piece appears by Brackens’ “the warmth of other suns” in “Friendship and Collaboration,” a section that Omotosho notes shows “influence as a kind of exchange” and “acknowledges a reciprocity between artists.” The hyper-realistic painting shows Brackens floating in a pool, water rippling gently around him. Despite its almost photorealistic nature, it’s easy to feel what the exhibition calls “a dreamlike quality” to the piece when examining its exploration of the dichotomy between what we share in our public and private lives through the nuance within Brackens’ expression.

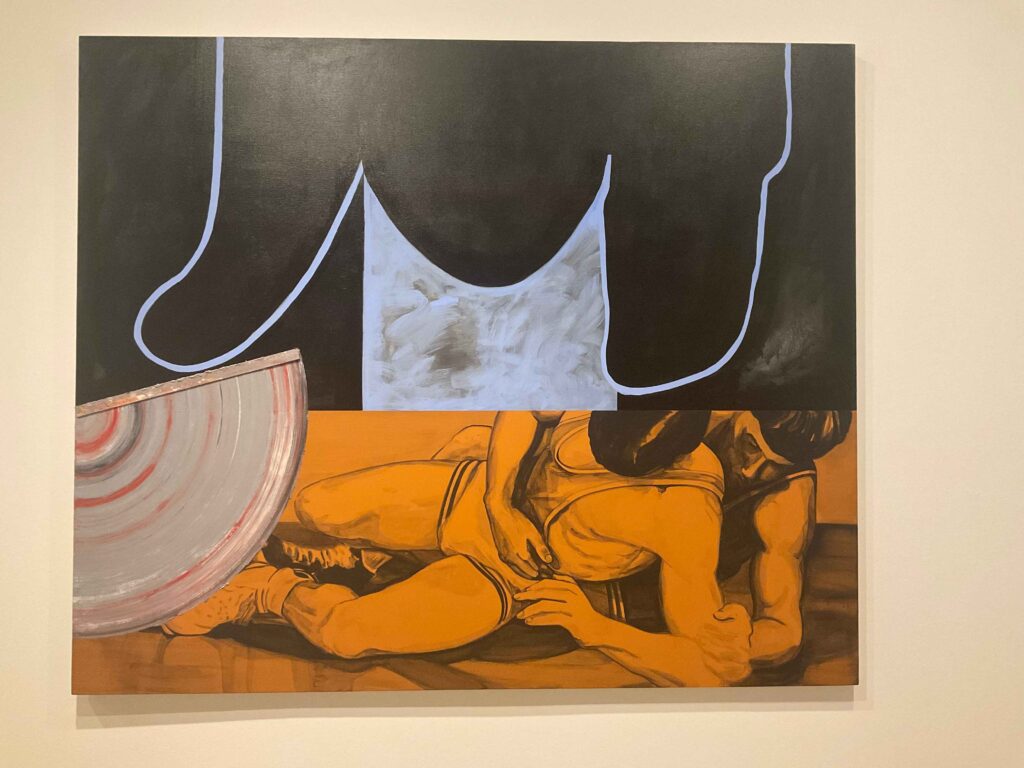

The exhibition recontinues a more rigorous critique of the standing of male artists in “Black Female Subjectivity.” In this section, the aforementioned “Elegy to the Spanish Republic 108” hangs aside Janiva Ellis’ “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” Omotosho refers to the pairing as an example of how “the non-chronological organization of the exhibition allows for certain juxtapositions between artworks.” “Consider the way Ellis and Motherwell approach the picture plane; their works issue from different time periods and yet are linked by a kind of formal and psychic preoccupation with the void,” Omotosho said. Additionally, the exhibition notes how Ellis’ piece serves as a critique of privileged creatives who seek out threats to spark their emotionally charged work.

That challenging of traditional narratives, even in a recent piece like Ellis’, speaks to the exhibition’s roots in the activism of the 1970s. Omotosho said the period offered a challenging of American Culture by “queer and feminist activities, writers and scholars whose work offered expansive and critical ways of understanding how race, gender and sexuality striate and shape the textures of everyday life.”

“Many of the artists in the exhibition came of age during this period, and one reward, I think, of the exhibition is the opportunity to consider how the legacies of this generation of artists have been taken up by their successors,” Omotosho said, referring to the five decades of work spanning the exhibition. “It also offers the opportunity to consider the continued relevance of liberation movements to our present moment, a moment as rife with inequities as any other. Artists are still finding ways to deepen and complicate our understandings of gender and race inequality in America.”

“He Said/She Said: Contemporary Women Artists Interject” runs through July 21 at the Dallas Museum of Art. For more information, visit https://www.dma.org/.